Haro Tissa supports her 11-person household in Burkina Faso by raising small livestock.

Sara Passman, USAID

Haro Tissa supports her 11-person household in Burkina Faso by raising small livestock.

Sara Passman, USAID

Haro Tissa supports her 11-person household in Burkina Faso by raising small livestock.

Sara Passman, USAID

Haro Tissa supports her 11-person household in Burkina Faso by raising small livestock.

Sara Passman, USAID

Speeches Shim

In 2016, the ONE Campaign summed up the many issues women and girls face in developing countries in its Poverty is Sexist report: “In too many countries, being born poor and female means a life sentence of inequality, oppression and poverty.”

Nowhere is this more the case than in the Sahel region of Africa, a vast portion of the continent that stretches from Senegal in the west to Sudan in the east. Maternal mortality and fertility rates are some of the highest in the world, and many countries in the Sahel rank at the bottom of the list for female primary school completion rates. According to the report, five of the 20 worst places to be born a girl are Sahelian countries.

How to overcome those dismal odds?

In Burkina Faso and Niger—both in the bottom 20 of worst places to be a girl, with Niger ranked the worst—local women participating in USAID’s Resilience in the Sahel Enhanced (RISE) program are playing a major role in helping their communities overcome health and food security obstacles, often serving as leaders. Let’s meet a few of them.

Chantal Yarga

Chantal Yarga is a mother of six children in Bangaye, in the East region of Burkina Faso. Yarga often found it difficult to care for her children and provide them with nutritious and filling meals. She and her husband rarely had enough money to take their children to the local health center, and, during bad harvest years, were unable to supply all their children with what they needed to thrive.

Two years ago, USAID’s RISE program started teaching people in rural Burkina Faso and Niger about conservation farming, or improved agricultural techniques that could help farmers produce more crops. When Yarga’s husband was unable to attend, she went in his place. At the training, she and other members of the group learned to build compost pits to enrich the soil in their fields, dig holes to catch water and concentrate nutrients, and other techniques for improving crop yields.

Yarga planted sorghum and millet using her newly acquired knowledge, and found that her crops grew faster and produced better yields. Instead of running out of grain just two or three months after the harvest, she and her husband had grown enough to feed the family for at least six months.

This year, Yarga joined a group that promotes animal fattening. With USAID’s help, the group learned techniques for raising sheep and goats. Yarga is currently raising two sheep, two goats and two cows; one of her sheep recently gave birth to three healthy lambs. Now, when she sells her animals, she will be able to make a profit.

“Now I understand the relationship between animals and agriculture,” she says. “My animal raising helps improve my compost, which I can use in my fields to grow better crops.”

The family is able to save their bigger crop yields for use or sale further into the year, and Yarga uses the extra income she earns from crop and livestock sales to buy more nutritious foods and pay her children’s school fees.

Yarga’s husband, Sambo, is proud of how healthy his family is now. Before, he said, the children were often tired and sick. Now, they rarely get sick, they sleep better, and they never have to go to the hospital. “You can see my wife’s success in how the children look,” he said.

N’walla’s Boss Ladies

A few years ago, USAID began helping women in N’walla, a village in the Maradi region of Niger, organize village savings and loan associations, and helped them learn about potential small business opportunities. Each group member contributes 100 fCFA, or about 20 cents per week. Members can take loans for small income-generating projects, like sewing or selling food, or can borrow money to pay for health care or clothing for their children. The women are expected to pay these low-interest loans back within four weeks.

While these individual loans were useful, one group of women became interested in working together to grow their economic independence—focusing on making products from nutrient-rich niebe, or black-eyed peas. Villagers were already growing niebe, but learned how to transform the beans into other products, making porridge, couscous and pasta from niebe flour, and even baking niebe cookies. Soon, the women began selling their niebe products at local celebrations, regional markets and agricultural fairs organized by the Nigerien Government and USAID. The group reinvests the profits they earn from their sales, renting land to plant more niebe and buying items that make the transformation process simpler.

The women have also planted a moringa garden. Moringa is a fast-growing tree, with leaves that are high in protein and vitamins. Through USAID’s training, the women now know how to harvest, dry and grind the leaves into a powder that can be easily added to traditional foods to make them more nutritious. The group is working with the local health center to sell moringa powder to pregnant and nursing women, making available important supplemental nutrients to the community members who need it most. And, like their profits from the niebe products, the money they earn goes back into their savings and loan fund.

The N’walla women’s group has become a model for other groups in the community. The group has won prizes at local agricultural fairs for their innovative recipes using niebe and moringa. Some of the women even give cooking demonstrations to their friends using the products they create.

The women have seen the positive effect their activities have had on the village. N’walla has a local committee that regularly monitors the village’s children for malnutrition. The women proudly point out that, since they started producing and selling their products, the committee rarely finds a case of malnutrition in the village.

“Before, we were more isolated. Now, we help each other succeed,” said Houre Maazou, a 20-year-old member of the group. “Now, we have the opportunity to receive credit and make our lives and our friends’ lives easier.”

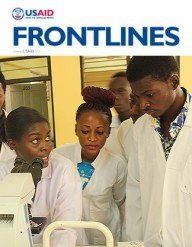

Haro Tissa

Haro Tissa lives in Margou, a village in the East region of Burkina Faso. Ten years ago, her husband went blind, and since then she has been the head of her 11-person household. Life was difficult. So when USAID started resilience-building activities in her village, Tissa was eager to participate.

She was particularly interested in habbanayé, a local custom of loaning a breeding cow, goat or other animal to a neighbor or family member in need. In this arrangement, when the animal gives birth, it is returned to its owner while the recipient keeps the baby for its milk and meat. The cycle continues as more breeding occurs, spreading the wealth of livestock throughout the community.

Chosen by her community to be a beneficiary of USAID’s habbanayé activities, Tissa received five goats during the 2015 rainy season. “I learned how to feed goats, produce mineral licks and grow enough livestock feed. I also learned to build sheds to protect the animals from the rain, and how to monitor the animals’ health,” she explained. After 14 months, Tissa’s goats had given birth to nine kids. She passed five of them to another woman chosen by the community.

For Tissa, the benefits from habbanayé were clear: “On a half hectare, I produced 25 bundles of grass and 24 fodder bales. I used them to feed my animals throughout the year. I used the animal droppings to make compost for my fields. Because USAID taught me the importance of using compost, I harvested 400 kilograms of millet, much more than in previous years.”

“I now harvest 300 liters of goat’s milk every year,” she continued. “I give the milk to my grandchildren, and I can see a difference in their health.”

Tissa has taught her daughter-in-law everything she learned from USAID, and her own daughter recently started raising goats. “I hope my daughter will breed these goats and get the same benefits,” Tissa says. “She could break the circle of poverty and help somebody else afterwards.”

Word is getting around and Tissa is now a local celebrity of sorts. “These activities brought me more self-confidence and social recognition in my family and my community,” she says.

Tissa acknowledges to other Margou women that some of the new practices take more work than they are used to, but that the hard work is worth it because of the benefits that will come to their families.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.